Young Academy of Finland and Belgian Young Academy co-organized in May 27, 2020, a virtual workshop on the future of science advice and its possible methods and forms in the EU. The issue of working relations between researchers and decision makers in all levels could not have been more topical in the midst of the covid-19 -pandemic. Just like many other workshops during Spring 2020, also this dialogical workshop was organized via Zoom. Please read further to learn some of the thoughts collected during the ”The Future of Independent Science Advice in the EU Ecosystem: How to make sure that research synthesis reports are read?” -workshop.

Creating systemic and long-term research synthesis/review reports is the prominent form of disseminating scientific knowledge for policy makers. For example, according to the data gathered as part of the Young Academy Finland’s “Young Researchers as Knowledge Brokers” project, over 80% of the European young academies used this method to deliver knowledge (mostly) for their national decision makers. Reviewing and synthesising existing scientific knowledge is also a method of delivering science advice in the current European Commission’s Scientific Advice Mechanism SAM where European science academies participate through its SAPEA element. Synthesis or reviews are seen as a good way to collect large amounts of current information into one package.

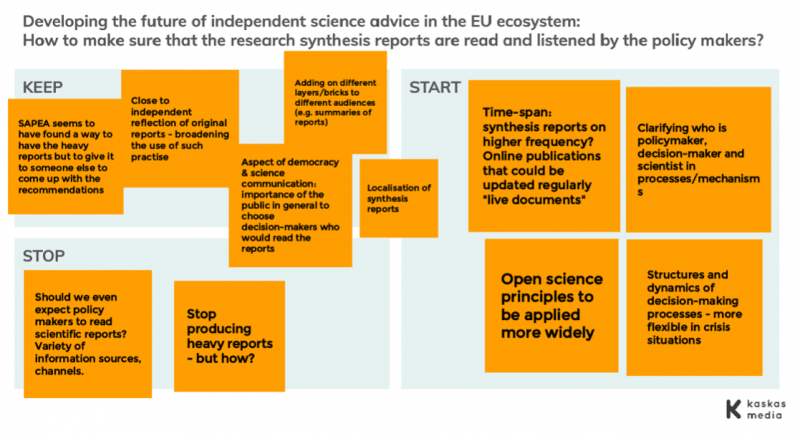

But are these research synthesis reports read? Decision makers often complain that synthesis are too thick and time-consuming to read. If the reports are read, is knowledge presented in them implemented to policy actions? The example of IPCC shows that big knowledge assessments do definitely have a role with setting things on political agenda, but research also confirms that there is no linear line that would lead even from strong scientific certainty straight to policy actions (see e.g. Wyborn et al. 2018 or Beck 2015). What we could do to make a better impact then? How we could present better synthesis?

According to the definition of Wyborn et al. (2018, 73): ”…research synthesis is conceptualised as a process of reviewing, assessing and synthesising existing literature or data to produce a series of outputs (products and services). Synthesis is often conducted by academic disciplinary experts, but can involve inter- or transdisciplinary working groups drawing on knowledge from across academia and beyond.”.

While scientists might be cautious of keeping their distance to decision makers in order to keep their integrity (see e.g. Pielke 2007), every research synthesis process, regardless of involving non-academic stakeholders in the work or not, does has its context, though, and hence it is not done in isolation (Wyborn et al. 2018). Synthesis process is not totally free from the politics either in the sense that the contents of it are dictated by choices relating to e.g. different synthesis methods or whose voices are counted in. There are also signs that engaging the end-users of knowledge in the process at least at some point (e.g. at least in the beginning or/and at the end) during the research synthesis projects actually adds the usability of the synthesis (Ibid).

How much distance there should be between knowledge and policy?

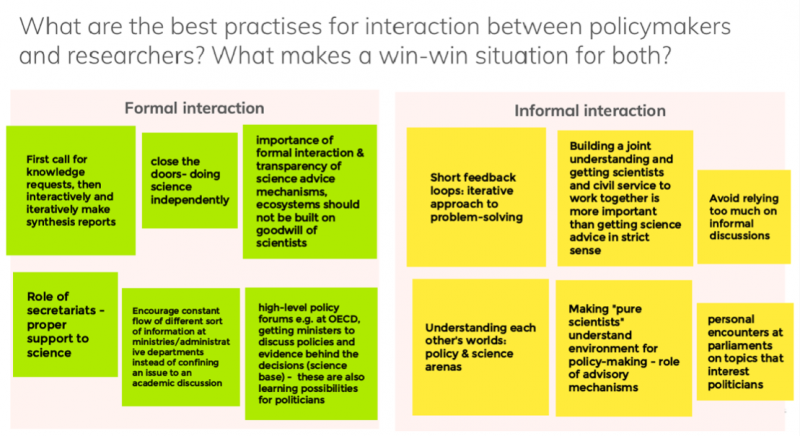

We asked from the participants of our workshop what are the best practices for A) formal and B) informal interaction between policymakers and researchers. Here are some of the comments we collected during discussions:

What we can read from the answers is that while formal channels provide continuity and lasting connections at the organizational level, informal interaction might answer to quick information needs better than often quite slow, official knowledge synthesizing projects. Informal channels also help to create mutual understanding and trust better than more linear and often quite parted “question-answer” -processes. Informal channels might also bring positive surprise factors, when decision makers might find interesting new disciplines or researchers hear original questions. Informal channels are great when discussions need to be started.

Research Director Tanja Suni from the Finnish Ministry of Environment challenged in her speech at the workshop called for more diverse methods & arenas of science-policy interactions in order to increase knowledge-informed policy making. She underlined that commissioning a traditional, so called linear report or a written synthesis works well when the problem to be solved is simple enough. She continued, that written report should also not be noticed as the only possible end-product of science advice, but also e.g. changed values or even changed emotions might be considered as a successful ending for the science-policy knowledge exchange.

Her notions are very apt. Scientific knowledge is facing a lot of challenges concerning its legitimacy, accountability and overall status in the society. The complexity and “wickedness” of many current political issues like the current pandemic, climate change, loss of biodiversity or ageing population, also demonstrate that the amount of scientific knowledge does not erase the tension between values and political decision making. Hence, by adding the possibilities for science-policy interactions also through informal and less strict ways and strengthening understanding & trust, we actually might help increasing the impact of science advice given. In the workshop discussions the following practices were often mentioned as important for sound knowledge-informed decision making:

- Multitude of knowledge sources and interfaces & noticing different decision maker groups (parliamentarians, ministries, officials, municipalities)

- Engaging directly with stakeholders

- Transparency & open science principles

- Flexibility

- Diversifying “the ideal type of science adviser” and acknowledging also younger researchers

- Supporting more transdisciplinary and multidisciplinary funding opportunities (best practice example from Finland is Strategic Research -funding instrument)

- Clarifying the roles and responsibilities between decision makers and researchers

Despite the interaction with decision-makers, scientific advice must retain its independence and integrity to ensure their credibility. Adding transparency to the process, engaging with stakeholders and stop relying that written reports speaks for themselves does not necessarily, however, mean “politicizing science advice”. One of the interviewed young academy representatives as part of the “Young Researchers as Knowledge Brokers” -project underlined the meaning of credibility along with quality of knowledge as follows: “So, it’s not just creating a paper and sending it to the policy makers. It’s creating a paper, sending it to policy makers, and following up on that, creating relationships, having discussions with the policy makers, but that important first step is demonstrating that you have knowledge and the ability to be objective and non-party political.“

Would there still be room for something new in the European Union ecosystem?

An introductory keynote to the EU science advice ecosystem was provided by Policy Officer, Dr. Kristian Krieger from the Joint Research Centre of the European Commission. Dr. Krieger admitted there are lots of sources of knowledge on the European arena and clearer definitions of roles of these diverse actors and the type of knowledge they provide might be needed in the future. Need for common guidelines and overall, general capacity building on possibilities and skills related to science advice was repeatedly mentioned in our workshop discussions, too. It was also stated several times, that the civil society should be taken better into account in the EU science advice mechanisms e.g. by organizing public hearings. This was considered important for creating trust and understanding towards scientific knowledge in general. European Science Media Hub, presented by Silvia Polidori in the workshop, does great work with science journalists and science communication in order to support high quality science communication at the Parliament and among European Union civil societies.

European Union’s bodies like the European Commission and European Parliament have currently strong in-house services to guarantee access to scientific advice. In addition to SAM, European Commission has e.g. Joint Research Centre JRC and numerous advisory committees in its service. Members of European Parliament can use the services of Panel for the Future of Science and Technology STOA or European Parliamentary Research Service EPRS, but MEPs also rely strongly on their national sources. Here, science academies and national boundary organizations might take more action and build stronger connections towards MEPs. One should not also forget the Council of the European Union, which relies almost solely on national information sources rather than any collective channel. Hence, both national and European-wide, collective channels are needed.

Our guest of honor during the workshop, Member of European Parliament Sirpa Pietikäinen reminded that MEP’s science literacy skills and also knowledge needs vary, which is another reason why there should be different methods for disseminating knowledge as well. She gave few handy tips for building impact for the research syntheses and science advice in general. First of all connecting right people is important, second, adapting messages to different audiences is essential and lastly, one needs to guarantee that knowledge is not just high quality in scientific means but that it is also usable & credible for the policy makers. A good example presented during the workshop on ways to build connections for trust and for listening the needs of national MPs is the action of Belgian Young Academy’s Science Meets Parliament -program. Similar programs have also been organized by STOA at the European Parliament.

Read the program of the May workshop

References:

Beck, Silke (2015): Science and experts in P. Pattberg, F. Zelli (Eds.) Encyclopedia of Global Environmental Politics. Edward Elgar. Pp. 234-240.

Pielke Jr, R. A. (2007). The honest broker: making sense of science in policy and politics. Cambridge University Press.

Wyborn, Carina, Louder, Elena, Harrison, Jerry, Montambault, Jensen, Montana, Jasper, Ryan, Melanie, Bednarek, Angela, Nesshöver, Carsten, Pullin, Andrew, Reed, Mark, Dellecker, Emilie, Kramer, Jonathan, Boyd, James, Dellecker, Adrian and Jonathan Hutton (2018): Understanding the Impacts of Research Synthesis. Environmental Science & Policy. 86, pp. 72-84. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2018.04.013